Introduction

Tsholotsho District is one of seven districts from Matebeleland North Province that participated in a Spark Health Africa Transformative Leadership & Culture Change Initiative in Zimbabwe. The intervention ran from January 2017 to December 2018. In Tsholotsho District, 10 District Health Executives were trained, and at least 200 frontline health workers from the 20 health facilities under its jurisdiction were integrated into the initiative. Although the Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission (PMTCT) intervention was the primary tracer program, Tsholotsho District expanded its application of Transformative Leadership & Culture Change principles to Maternal and Child Health.

Background

At the height of the social and economic crises that Zimbabwe faced in 2008, the public sector provided 65% of health care services. The severe social and economic challenges from more than a decade ago have resulted in an unprecedented deterioration of health care infrastructure, loss of experienced health sector personnel, and a drastic decline in the quality of health services available for the population. The fallout from this crisis manifested as demotivated health workers at best presented for work passively, and at worst, absconded from work through industrial action. Within this context, Spark Health Africa first introduced its Transformative Leadership & Culture Change model in Zimbabwe.

The mentoring and thought-partnership phase of the Transformative Leadership & Culture Change initiative had two objectives. The first was the transformation of the leader at the individual level. The second was transformation at the team level to influence system changes that would impact health outcomes.

The problem

Before the TLCC initiative, the Tsholotsho district health management team was characterized by dissatisfaction in the workplace because of an unhealthy structural and psychological environment, a dwindling sense of the value for their work, deficient support and mentoring, scant professional stimulation, and a perceived lack of appreciation from superiors. In turn, this toxic environment affected organizational outcomes that manifested as poor organizational citizenship behavior, lack of commitment and effort towards in-role performance, which also contributed to programmatic performance.

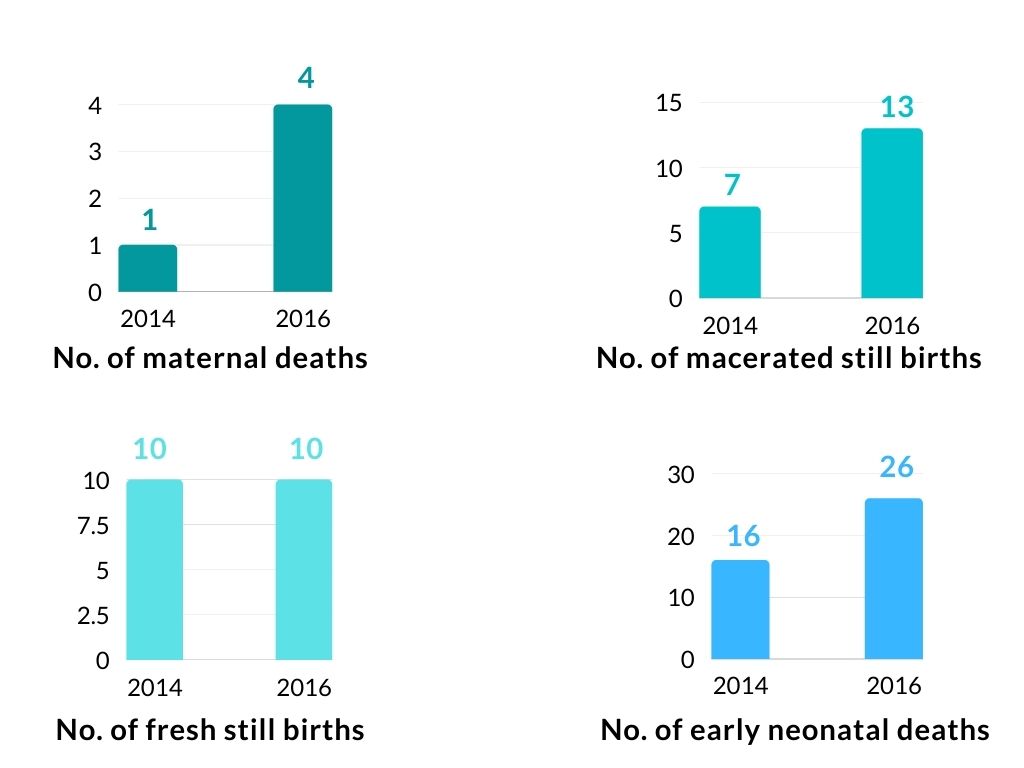

During the same period, at a program level, maternal and child health outcomes were progressively worsening.

Tsholotsho district maternal and neonatal indicators 2014 and 2016

The approach to addressing the problem

This poor state of outcomes created a sense of urgency within the Tsholotsho District Health Team to change. Tired of the status quo, in which clinical interventions alone yielded worse outcomes, the DHT took a different approach to address the team-based and program-based challenges it was facing.

The maternity ward at the district hospital is an example of one area where culture shift was most visible—The DHT strategy comprised of three interventions.

Intervention 1- Creating a culture of accountability that is underpinned by a psychologically safe working environment

The first behavioural intervention entailed creating a culture of accountability underpinned by a psychologically safe working environment where every team member- from the cleaners to the ambulance driver, through to the District Medical Officer- is held accountable for their actions.

The first part of creating a psychologically safe environment started with the Matron examining her approach to management and interpersonal relations:

I was a tough one! I didn’t listen to what other [subordinates] had to say. After the training, I started having meetings with my subordinates- which we do every Monday- to sit down with everyone to hear their views on work- from the cleaner to the senior nurses.

Everyone now is not afraid to speak their mind. Previously, the general hands did not participate because they felt they were not part of the team…[Now] Motivation is very high in the maternity ward…people feel empowered to do their work without waiting for instruction from me

Sister Viola Dube, Matron, Tsholotsho District Hospital Maternity Ward, 27 November 2018

For the Tsholotsho District Health Team, accountability for actions did not come from fear of losing their job. Instead, they understood the risk that a mother or baby might lose their life if the team did not collectively do what they are supposed to at the appointed time. Working in the same community where they lived, amongst people they met after work, created a sense of greater good and tangible impact.

Intervention 2- Developing a highly effective team

Maternal and infant deaths are rare, often having long intervals between successive events. The good intentions alone of being accountable for deaths are not good enough even when events are spaced far apart. Because of the lack of routine, health teams may lose their touch. The Tsholotsho District Health Team recognized this gap and acted on it.

The first part of developing a highly effective team entailed creating dependability, where members get things done on time and meet expectations of the services they rendered. High-performing teams have clear goals and have well-defined roles within the group. For Tsholotsho District, the goal was zero deaths. To reinforce members’ roles in their minds and provide intellectual stimulation between rare deaths in the maternal wards, everyone had to participate in mock Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) drills. This exercise empowered staffers to influence processes and procedures in their workspaces, promoted consistent practices and built teamwork in preparation for real-life situations.

Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) drills

Doing the on-job-training [drills] has helped the team find out where a particular skill was missing. But we have always done this, [only that previously] we just did it as a routine, but after seeing that we could have prevented a baby death, the difference now is everyone is careful about doing what they have to do to save the mother and child.”

Sister Viola Dube, Matron, Tsholotsho District Hospital Maternity Ward, 27 November 2018

Intervention 3- Creating motivation through institutional justice

GThe social and economic challenges prevailing in Zimbabwe were no stranger to Tsholotsho District. In fact, because of its isolated location, these vices manifested more as institutional injustices. Subordinates reported that supervisors were known to withhold information and unfairly distribute opportunities to attend training and workshops, which were always associated with financial allowances. They also noted that supervisors would inequitably avail themselves to coach and mentor subordinates. All these injustices created a sense of “them-&-us.” When poor outcomes occurred, such as a maternal or infant death, no one, and certainly not the team, wanted to take responsibility.

As a third intervention, the first thing that senior leadership did was commit- almost overnight- to support subordinates equally. Previously, the senior clinicians routinely walked through the maternity ward attending to patients without addressing staff. Daily, senior clinical officers did their maternity ward runs together, ensuring they spoke to every staff member about how they were getting along with their duties. They knew that there would be mistrust at first, but by humbling themselves and putting themselves in their subordinates’ shoes, they were determined to stop and reverse injustices. The outcome of this intervention was a self-motivated team that recognized the empathy shown by senior leadership, and in turn, committed to working selflessly beyond the call of duty.

The Reward- Improved health outcomes

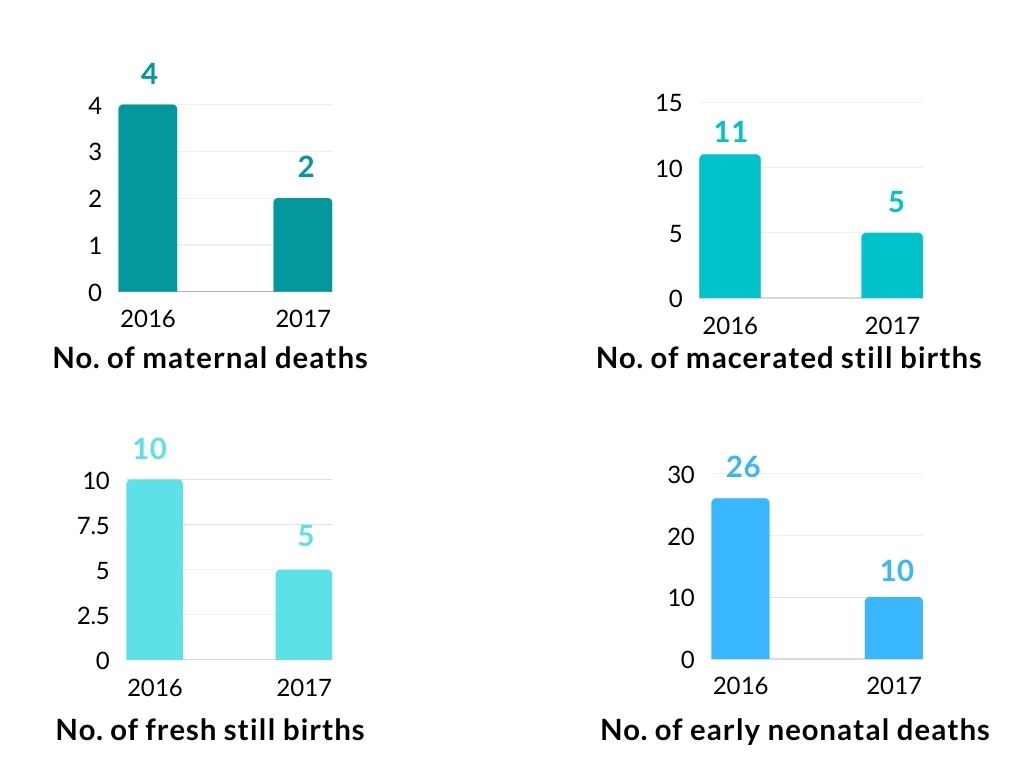

After 12 months of implementing the raft of culture change action plans, maternal and child outcomes improved:

Tsholotsho district maternal and neonatal indicators 2016 and 2017

What to read next from Spark Health Africa: