Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic unleashed an unprecedented wave of trauma on the one hand and waves of creativity and collaboration amongst public health professionals across Sub-Saharan Africa on the other hand. Funders1 and implementing agencies2 have welcomed this creativity and collaboration by supporting the establishment of Innovation Platforms to better understand emergency responses to COVID-19 and to achieve progress on long-term health priorities across the region.

Since April 2021, Spark Health Africa has been leading the implementation of the Learning Network for Scaling Innovations in the Public Sector Across Sub-Saharan Africa3 to build on this momentum. The purpose of the platform is to build strong relationships and create opportunities for sharing best practices, develop tools based on evidence-based practice and solutions that can be used in the public health sector. To this end, Spark Health Africa held a series of webinars under this body of work. The first event, titled, Re-engage with the Learning Network: Creating a Platform for Collective Impact, sought to connect (new and existing) members with the vision of the Learning Network to generate excitement through participation in the Learning Network’s interactive events. The second event, titled, Looking beyond COVID-19: Turning Emergency Response into Sustainable Impact, was hosted by the Skoll World Forum, where a panel from the governments of Uganda and Cote d’Ivoire shared verifiable examples (case studies) of how these governments, with support from implementing partners, located in LMIC settings implemented emergency COVID-19 programs with a sustainability lens to support long-term health system priorities. The third event, titled, Transformative Leadership for Public Sector Scaling on Innovations, brought together a broad panel of experts from governments, funders, and implementing partners to share their insights on readiness to scale, and how they organize themselves to scale. These conversations contributed to the creation of a framework that shows how a shift in thinking, methods and execution builds a functional system that supports scaling of solutions in the public sector. The fourth event, titled, Key Learnings From Public Sector Scaling Of Innovations In East Africa, built on the prior event and brought together a panel of experts representing governments and implementing partners from East Africa to share their observations on the mindset required to apply scaling frameworks and tools in the context of East Africa settings.

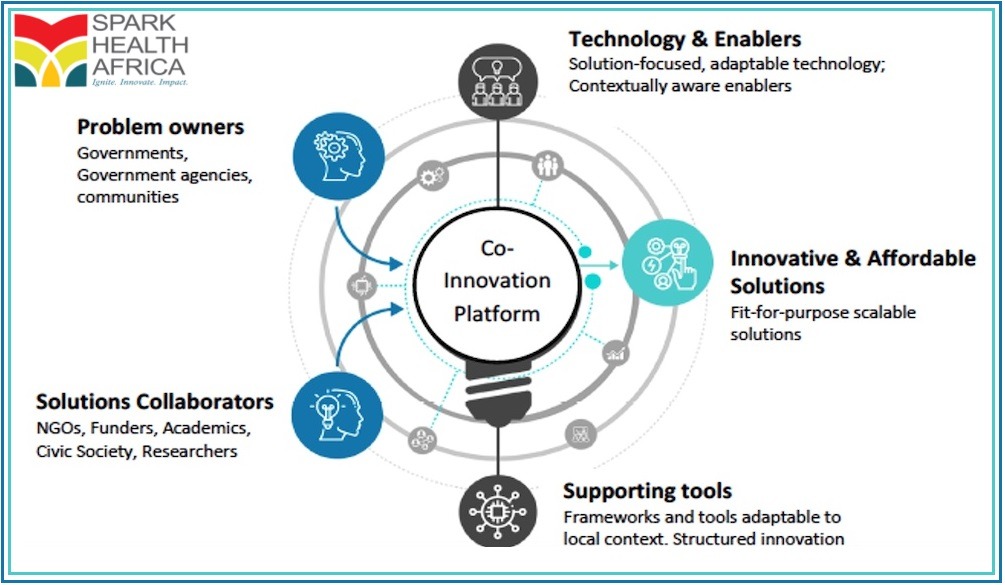

Recognizing that a lot has been “said”, not just on the Learning Network but widely on other global platforms such as the Global Community of Practice on Scaling Development Outcomes4, about what public sector scaling of innovations is and the requirements for successful implementation, Spark Health Africa advocates for Co-Innovation Platforms as a practical vehicle for catalysing the scaling of health innovations in the public sector. A Co-Innovation Platform is a space for learning and change where a group of individuals (who often represent organizations) with different backgrounds and interests come together to develop a common vision and find ways to achieve their goals. It is with this background that Spark Health Africa hosted a panel of experts from governments, funding partners, implementing partners, and the private sector for a webinar, titled, Co-Innovation Platforms for sustainable transition to scale: moving from talk to action, to share their observations and insights on whether Co-Innovation Platforms are indeed helpful in building the capacity of the public sector (chiefly, governments) to sustainably scale innovations, and if so, the mechanisms through which this has or can be achieved. In the sections that follow, we share the observations, experiences, and insights from the diverse panel of speakers.

Managing interests and power dynamics when setting up a Co-Innovation Platform

Innovation and certainly innovation platforms are not new, but over the last couple of years both have received heightened attention as scaling stakeholders have sought mechanisms to promote sustainable scaling through the public sector. While anyone (whether government, funder, Academia, implementing partner, or civic society) can initiate an innovation platform with a view to test and refine solutions for implementation and scale up, many initiatives have not succeeded as intended because of lack of the right composition of stakeholders and lack of clarity on the focus of the innovation platform and the range of options of the vehicles through which change can happen.

The first question fielded to the panellists was, “From your observations and experience from the platforms that you’ve initiated, facilitated, or participated in, what factors give rise to power imbalances amongst stakeholders (who, in theory, should be equal partners), and can you give examples of mechanisms that have successfully restored balance?” Easter Okello5 was of the view that Co-Innovation Platforms that are not universally open to everyone (emphasis added) or diverse enough result in minority interests not being represented. Network and relationship dynamics where strong pre-existing networks and relationships between certain stakeholders exist can create power imbalances. If one stakeholder has closer ties to influential individuals or organizations, they may wield more power and leverage within the Co-Innovation Platform. This misrepresentation of interests may be further exacerbated when differences in legal and regulatory frameworks can impact power dynamics. For example, intellectual property laws may favour certain stakeholders, granting them more control over the outcomes of co-innovation activities. Easter’s remark on governments at times showing a Big Brother syndrome- alluding to unfairly favouring select funders of implementing partners (and by extension, their interests), took the audience by surprise, but was a refreshing admission of behaviour that is known but not publicly acknowledged as a source of power imbalance.

Responding to the same question, but offering an opposing view, Thomas Feeny6 noted that it is more important to have the right composition of people (or organizations) with the requisite interests and influence at the right time/stage rather than every possible contributor every time. It’s not enough to have warm bodies filling seats at the table- their contribution in terms of ownership and effort (as shown by their motivation and time contribution) also counts. In Jane Soko’s7 view, the lack of government ownership and buy in creates a vacuum that those with stronger interests or greater commitment will fill. Patrick Mugisha8 echoed this view, affirming that different levels of engagement by members (early adopters vs. laggards) of Co-Innovation Platforms can cause misalignment in efforts that further deepen power imbalances between those who are more visible and vocal than others.

On remedies for managing interests and power dynamics, most responses from the panellists were of a technical nature. Adetunji Eleso9 pointed out the importance of stakeholders having a common understanding of what innovation is and the different stages of the scaling process. He added that, with this common understanding, it is essential that those who are closest to the challenges that innovations seek to address need to be involved in informing the scaling process by establishing collaborative processes that allow transition along the different scaling stages. Adetunji closed his remarks by emphasizing the importance of the government to clearly articulate its needs, commit to public funding (in cash or kind), and prioritize where those resources are spent in the local system with a view to organically sustain scaling efforts. Providing insights on more normative solutions, Thomas Feeny and Patrick Mugisha respectively shared their thoughts on how stakeholders must be upfront in sharing their fears and assumptions, and how transparency at the initiation stage of the platform helps reduce mistrust and creates a potential pathway towards sustainability.

Learning and Capacity Building through Implementation

One of the most important things that innovation platforms do is to directly or indirectly build the capacity of their members to get things done. The tangible results of Co-Innovation Platforms are a result of the invisible product that is the capacity developed.

The second question fielded to the panel of experts asked, “In your experience, can you share with us examples of specific capacities that have been developed directly or indirectly by the innovation platforms you have initiated, or participated in?” Kathi Hanifnia10 shared her thoughts on how members of Co-Innovation Platforms across the board need to develop capacity for adaptability and flexibility to respond to changing circumstances, iterate on their ideas, and adjust their approaches based on feedback and insights gained during the co-innovation process. According to Kathi, this capacity for adaptability and flexibility will allow innovators to understand where they fit in and how best they can support government innovation and scaling priorities; governments to understand an innovation and its benefits and what it will take to institutionalize and scale; and development partners to find the best ways for supporting local needs. One technical capacity that Co-Innovation Platforms helps members develop is user-centric design through understanding the different pathways that scaling can take. Kathi remarked that by understanding the difference between when to innovate for scale and when to innovate at scale, members learn to understand user needs, gather feedback, and iterate on their solutions to ensure they address the real-world challenges faced by the end-user. Kathi closed by sharing how Co-Innovation Platforms support government members in particular to develop the capacity for collaboration and teamwork through soft competencies such as big picture thinking, mindset shift and envisioning the future, and technical skills such as self-organization. Asayya Imaya11 affirmed that Co-Innovation Platforms do indeed help members to develop the capacity to have big picture thinking beyond turf wars and egos to foster collaboration and teamwork.

Impact and Sustainability

On account of the complexity of the social challenges that Co-Innovation Platforms aim to address, it is not easy to demonstrate impact. Also compounding this measurement conundrum is that at times funders pursue short-term goals when in practice Co-Innovation Platforms require a long-term perspective to demonstrate impact.

It is against this background that the final question fielded to the panelists asked, “Can you share in your experience how you have gone about demonstrating impact or convincing stakeholders to take a long-term view of innovation platforms?” One perspective promotes systems thinking in the measurement of impact. In this regard, Kathi shared an interesting perspective on how Co-Innovation Platforms dealing with complex social problems can estimate social return on investment by adopting an outcomes mapping framework coupled with social impact forecasting methodology to balance short-term outcomes shown by current data against impact that will emerge in the future that will be contributed to by current scaling efforts. Thomas shared another view on the perspective that members of Co-Innovation Platforms have on impact and value. Thomas shared his thoughts on how stakeholders need to interrogate the different value addition outputs along the innovation scaling chain, recognizing that stakeholders value different parts of the innovation scaling process.

One view is that participatory policy making helps ensure the growth and continuity of ideas around solutions. in this respect, Easter shared her thoughts on the need for stakeholders to leverage existing public sector structures to embed sustainability in the scaling efforts of Co-Innovation Platforms. Closing off the discussion, Jane echoed similar thoughts around fashioning public sector structures, policies, and guidelines to support scaling on the premise that governments shift their mindset for scaling from just being a recipient to an investor in public sector system infrastructure.

Conclusion

In and of itself, this webinar event raised important issues around the initiation of Co-Innovation Platforms, their capacity building potential, impact and sustainability. Addressing power imbalances in a Co-Innovation Platform requires fostering open and transparent communication, creating mechanisms for equal participation, and implementing governance structures that promote fairness, inclusivity and sustainability. The technical and behavioural capacities that Co-Innovation Platforms help develop have long-lasting effects beyond the co-innovation platform, benefiting participants in their future endeavours and contributing to the broader innovation scaling ecosystem.

Beyond this webinar event, it is Spark Health Africa’s intention to recommend Co-Innovation Platforms as a vehicle that effectively promotes a deliberate engagement process of African governments, civil society, communities, development agencies, funders, researchers and universities to create collective experience that spurs the co-creation of impactful public health solutions that are difficult to achieve while working independently.